A Core Network Is Not a Product List

Switch – Firewall – AP selection, integration, and capacity reality

Most enterprise network projects start at the same point: product selection. And most of them break at the same point: products that do not work well together. Because what we call a “core network” is not three boxes (switch, firewall, access point) standing side by side; it is those three boxes carrying identity together, producing segmentation together, enforcing policy together, and most importantly, sustaining operations together.

What I have observed for years is this: companies do not suffer because their network is bad, but because the network’s decision-making mechanism is fragmented. The most expensive devices, the best licenses, the highest throughput… all are there; yet when an incident happens, who knows what, which device decides based on which context, where traffic is separated, where it is controlled—there are no clear answers. The result: “there is a network,” but there is no “network behavior.”

In this article, I will examine the core network across three pillars: Firewall, Switching, and Access (Wi-Fi). But before that, I want to clearly state one thing: in the selection process, there are two factors that are just as decisive as “technical specifications,” and most teams realize them too late: reports/validation and support/lifecycle.

Filtering reports, tests, and “marketing noise”

One of the references to look at when selecting a product is, yes, Gartner reports. Because reports like Gartner give you an idea of a product’s “position in the market”: who is a leader, who is a visionary, who plays in a niche. This is especially useful for convincing decision-makers; it provides a framework for answering the question “why this brand?” at the budget table.

But there is a critical trap here: Gartner does not tell you which product is right for your specific scenario. Gartner is a “market map”; your job is to draw an “architectural map.” That is why it is more accurate to use Gartner as an initial filter: it narrows down options but does not make the final decision.

In addition to Gartner, performance and security tests conducted by vendors or independent laboratories, comparative reports, and “real-world” benchmarks must also be considered. Because the throughput listed on a datasheet is not the same as the throughput achieved in real life when IPS is enabled, SSL decryption is active, and application control is running. Reports serve as a second filter here: you look for a non-marketing answer to the question, “What does this box do under this load?”

Support and lifecycle: the invisible column that keeps the project standing

Just as critical as a product’s technical capabilities are its support model and lifecycle. Because network design is not limited to “installation day.” The real issue is what happens three years later:

- What are the EoL / EoS dates of this product?

- How fast are patches, bug fixes, and security updates delivered?

- Is TAC/Support truly accessible, and how does the escalation process work?

- What is the reality of RMA processes and spare parts availability?

- Does the licensing model create surprises after one year?

- Is the vendor roadmap aligned with the direction you are heading?

I want to emphasize this because the most common problem I see in the field is this: the team selects a product that is technically close to the right choice, but due to support/lifecycle issues, operations turn into a nightmare after 12 months. Then the blame is placed on the device; whereas the real problem is not the device itself, but the lack of seriousness given to the “support” side of the decision.

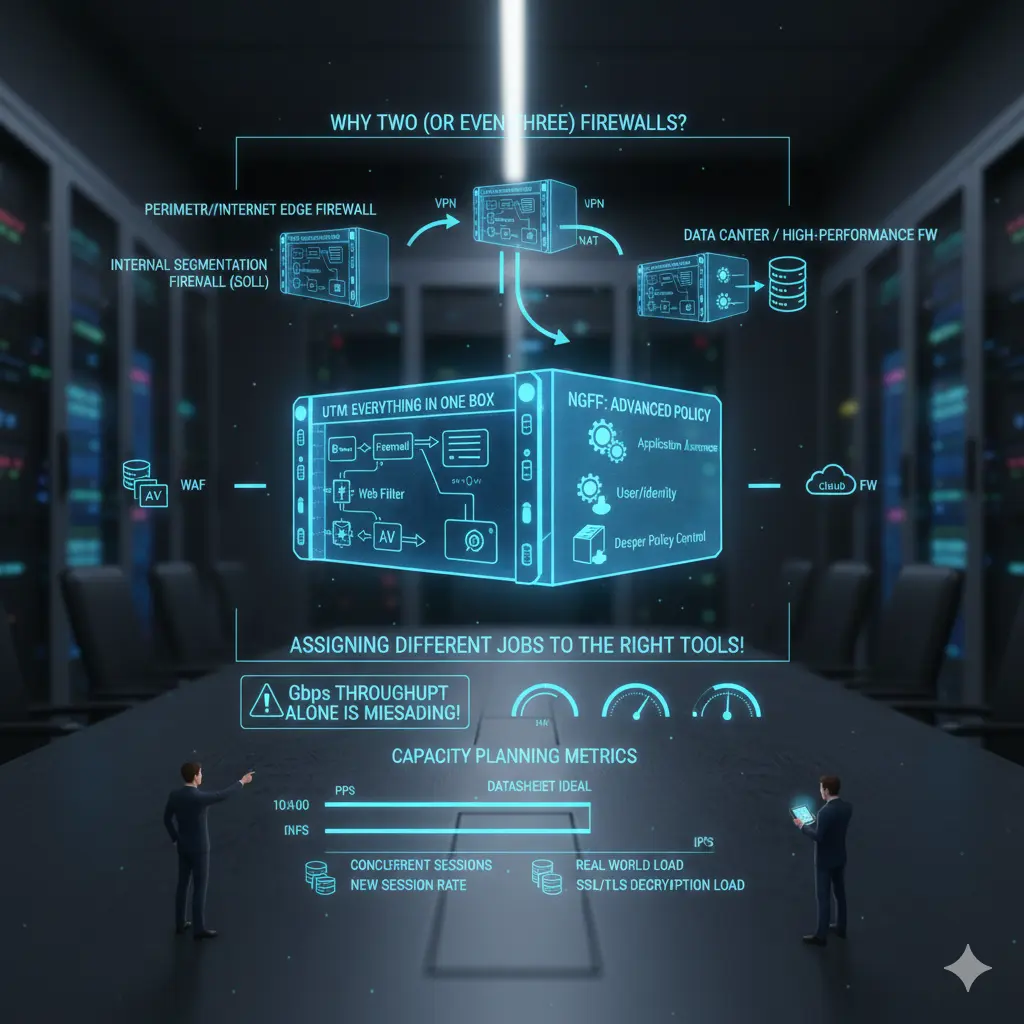

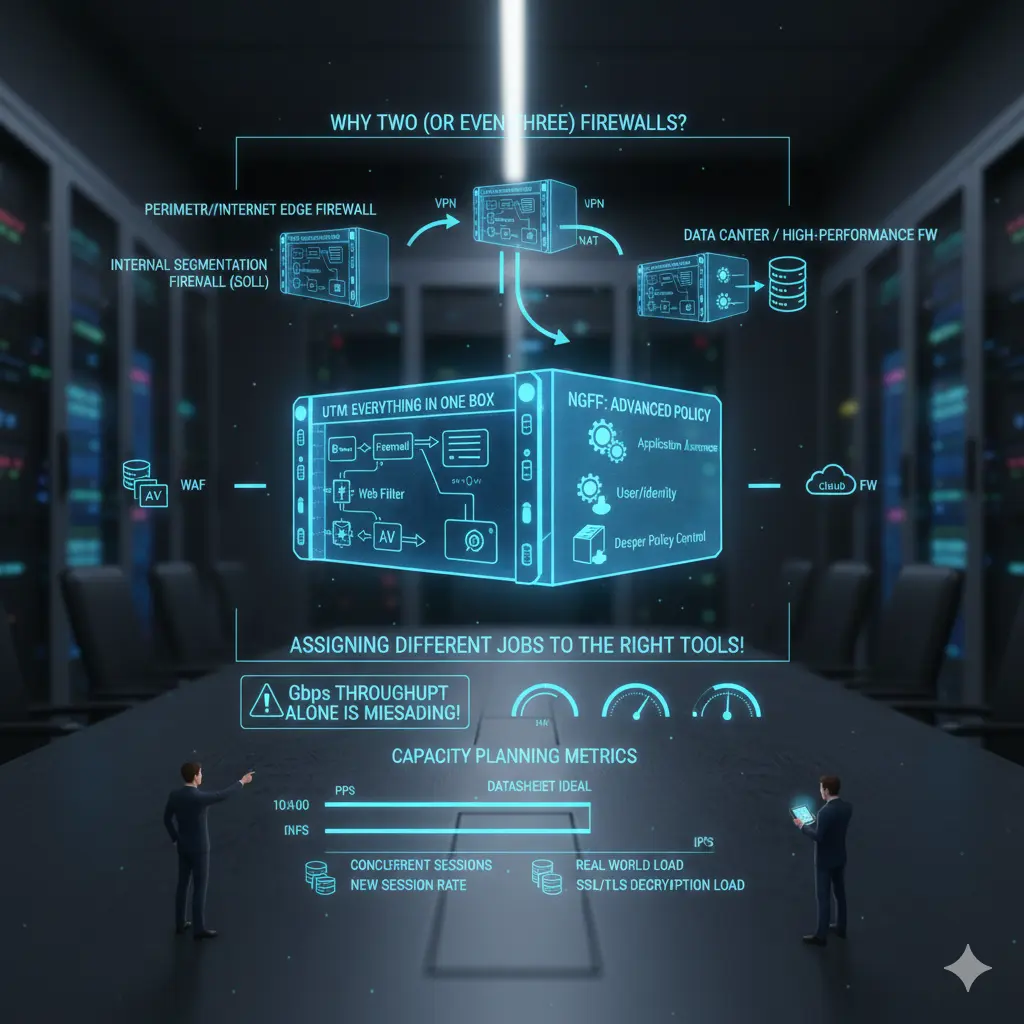

Firewall: UTM, NGFW, or multiple roles?

A firewall has long ceased to be merely a “security device at the edge of the network.” When positioned correctly, it becomes the policy brain; when positioned incorrectly, it turns into a bottleneck because everything collapses onto it.

It is useful to clarify terminology from the start: UTM and NGFW are often mixed up in many environments.

The UTM approach generally aligns with the idea of “everything in a single box”: basic firewall + IPS + web filtering + AV + some gateway features… Especially in small to mid-sized environments, it is preferred due to ease of management and bundled offerings.

NGFW, on the other hand, is positioned around application awareness, user/identity awareness, more advanced security services, and deeper policy control. In today’s enterprise needs, running security based solely on port and protocol is often insufficient; this is where NGFW comes into play.

But the most critical point is this: a company’s needs may not be satisfied by a single “type of firewall.” Because what we call a firewall can actually take on different roles at different layers for different purposes.

Why is it normal to have two (or even three) firewalls in the same company?

In many organizations, the following scenarios are very reasonable:

- Perimeter/Internet Edge Firewall: Internet access, VPN, NAT, inbound/outbound policy.

- Internal Segmentation Firewall (ISFW): Internal network segmentation, east-west control, critical zones.

- Data Center / High-performance FW: DC traffic, high session count, high PPS, low latency requirements.

- In some architectures, additional components such as WAF or Cloud FW.

This does not mean “buying two firewalls”; it means “assigning two different jobs to the right tools.” When you pile everything into a single box, you lose either performance, manageability, or security. Usually, at least one of the three is lost.

And this takes us directly to capacity planning.

Firewall capacity planning: throughput alone can be misleading

The most dangerous mistake in firewall selection is looking only at the “Gbps throughput” number. Because in real life, what kills a firewall is often not throughput:

- PPS (packets per second)

- Number of concurrent sessions

- New session rate

- NAT tables and state handling

- Performance with IPS/AV/App-ID enabled

- Heavy workloads such as SSL/TLS decryption

- Log generation and log transport (SIEM integration)

A real example: the statement “we bought a 10 Gbps firewall” means nothing by itself. Because that 10 Gbps is measured under “ideal conditions” in most vendor datasheets. In your environment, if IPS, URL filtering, application control, and decryption are enabled, the actual capacity changes dramatically. That is why the right question should be: “With the security features I will enable, and with my traffic characteristics, how much load can this firewall actually handle?”

If there is no answer to this question, the selection is risky.

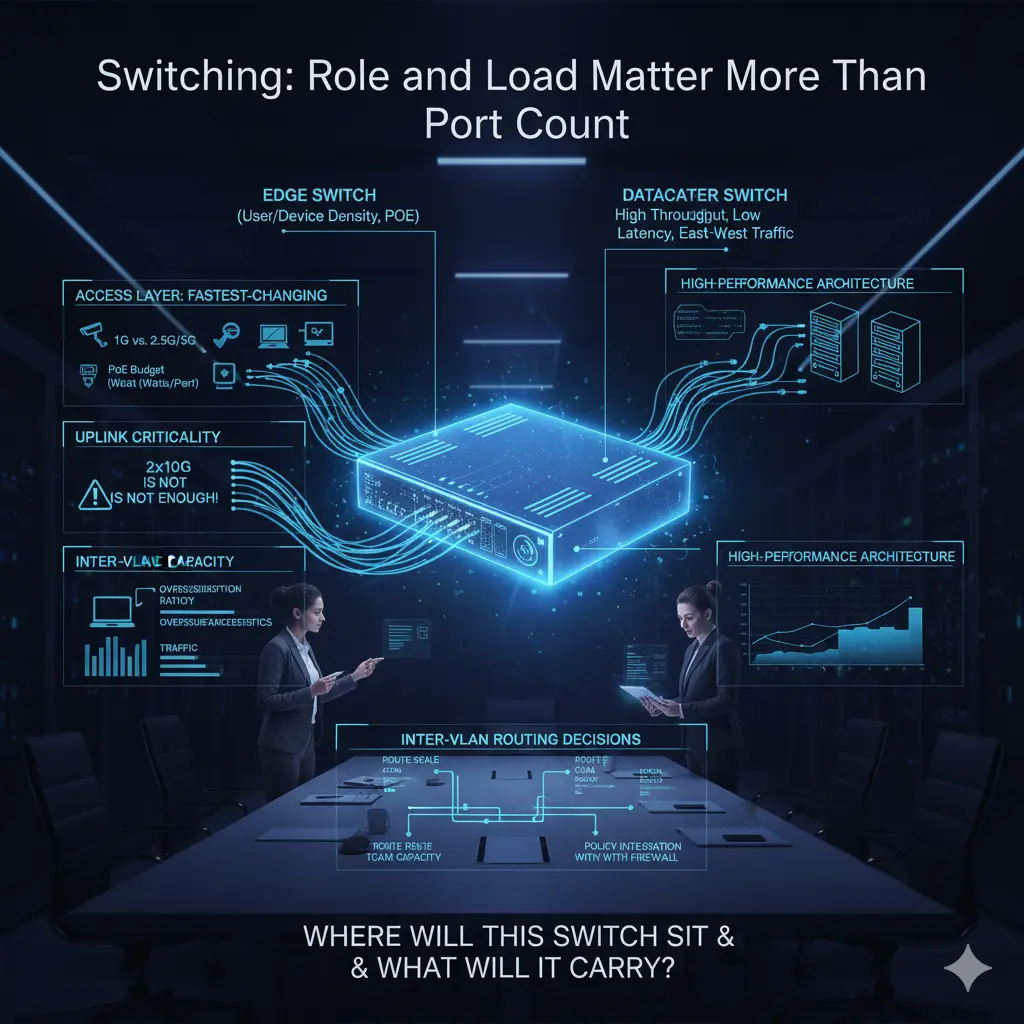

Switching: role and load matter more than port count

Switch selection often starts with port count: how many copper ports, how many fiber ports, whether PoE is needed or not… These are of course important, but from a core network perspective, they are not sufficient. Because a switch is not just a power socket connecting endpoints; it is a decision point that determines where traffic concentrates, where it separates, and where it is carried upward.

One of the most common mistakes on the access switch side is planning based on today’s needs. Yet the access layer is the fastest-changing layer in the network. A location that seems fine with copper ports today may host a high-bandwidth AP, a camera, or a different edge device tomorrow. Therefore, the speed capability of copper ports (1G vs. 2.5G/5G), the sustainability of PoE budgets not only in total watts but per port, and the real capacity of uplinks become critical.

The uplink topic is often underestimated. Statements like “2×10G uplink is enough” are frequently heard, but the traffic characteristics those uplinks will carry are rarely discussed. As user counts increase at the access layer and east-west traffic and broadcast behavior change, uplinks can reach saturation much faster than expected. At this point, it is necessary to look not only at uplink speed but also at the switch’s backplane capacity and oversubscription ratios. Because an uplink may be 10G, but if the internal architecture of the switch cannot sustain it, the bottleneck is inevitable.

The difference between edge switches and datacenter switches is also not clearly defined in many projects. Edge switches are typically optimized for user and device density: many ports, PoE, access-focused features. Datacenter switches come with architectures designed for high throughput, low latency, high PPS, and east-west traffic. Expecting both roles from the same device often either unnecessarily increases cost or delivers performance below expectations. When designing a core network, the question “where will this switch sit and what will it carry?” should come before “how many ports does it have?”

Inter-VLAN routing decisions are also directly related to switch selection. If routing is to be performed on the switch, it is not enough for the switch to simply support Layer 3; route scale, TCAM capacity, policy applicability, and how these decisions integrate with the firewall must be considered. Otherwise, a design that initially appears to deliver performance gains can later turn into an unmanageable complexity.

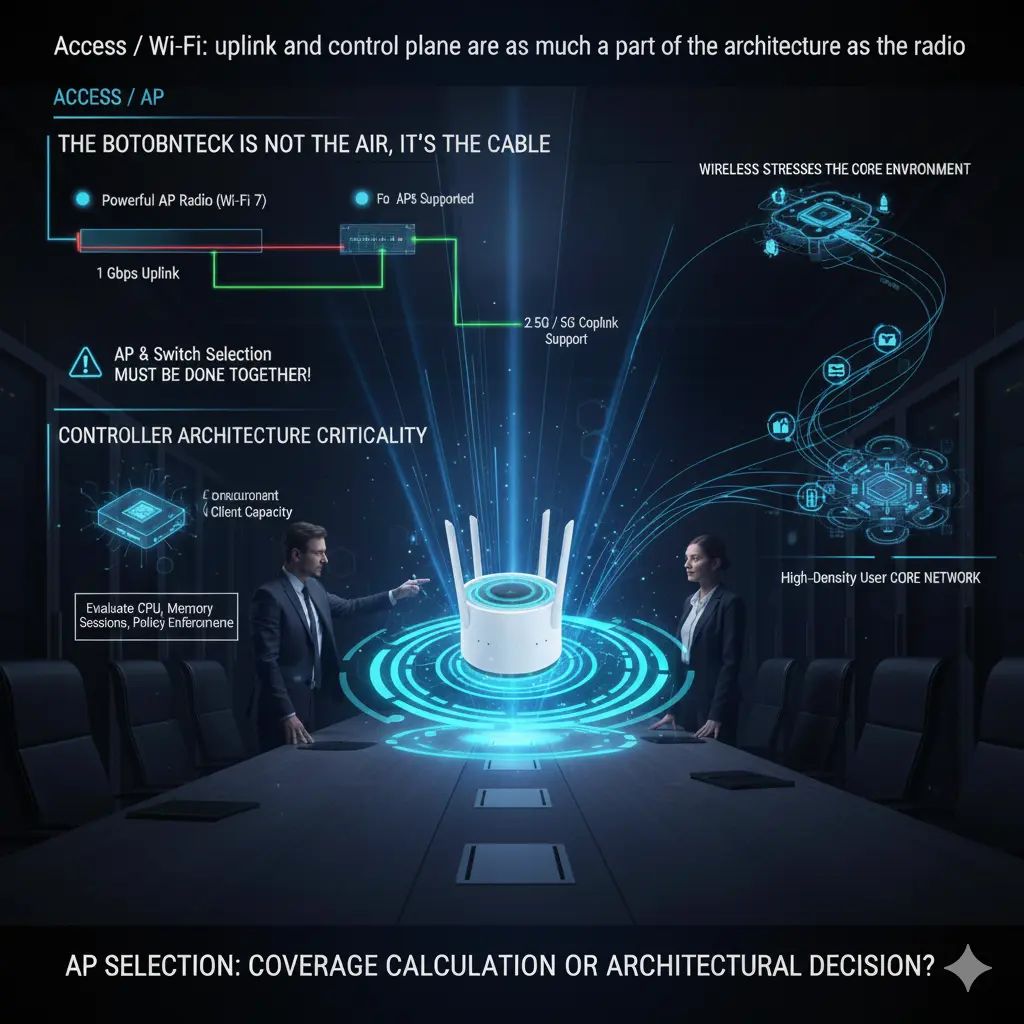

ACCESS / AP

Access / Wi-Fi: uplink and control plane are as much a part of the architecture as the radio

When wireless networks are discussed, the focus usually shifts to Wi-Fi standards: Wi-Fi 6, 6E, 7… Yet in practice, wireless performance is often limited not by the air, but by the cable. No matter how powerful an access point is, if the uplink behind it cannot carry the load, theoretical speeds mean nothing.

Today, many enterprise APs cannot utilize a significant portion of their potential when limited to a 1 Gbps uplink. That is why 2.5G and 5G copper uplink support is not a “luxury” but a direct design requirement, especially in high-density user environments. But here, too, the chain must not break: an AP may support 2.5G, but if the switch port it connects to does not, the entire investment is wasted. That is why AP and switch selection must be done together, not separately.

Another critical topic on the Wi-Fi side is controller architecture. The number of APs supported by the controller, concurrent client capacity, and roaming behavior determine the real-world stability of the network. A controller that claims to “support 500 APs” on paper may struggle much earlier in a high-density environment requiring fast roaming. Controller capacity must be evaluated not only by license count, but together with CPU, memory, session handling, and policy enforcement capacity.

Wireless networks are often thought of as “edge,” but in reality, they are the layer that stresses the core network the fastest. Users are mobile, connections are frequently dropped and re-established, and authentication and policy enforcement cycles are far more intensive than in wired networks. That is why a small design mistake at the access layer can create unexpected loads in the core network. AP selection is not just a coverage calculation; it is an architectural decision that directly affects core network behavior.

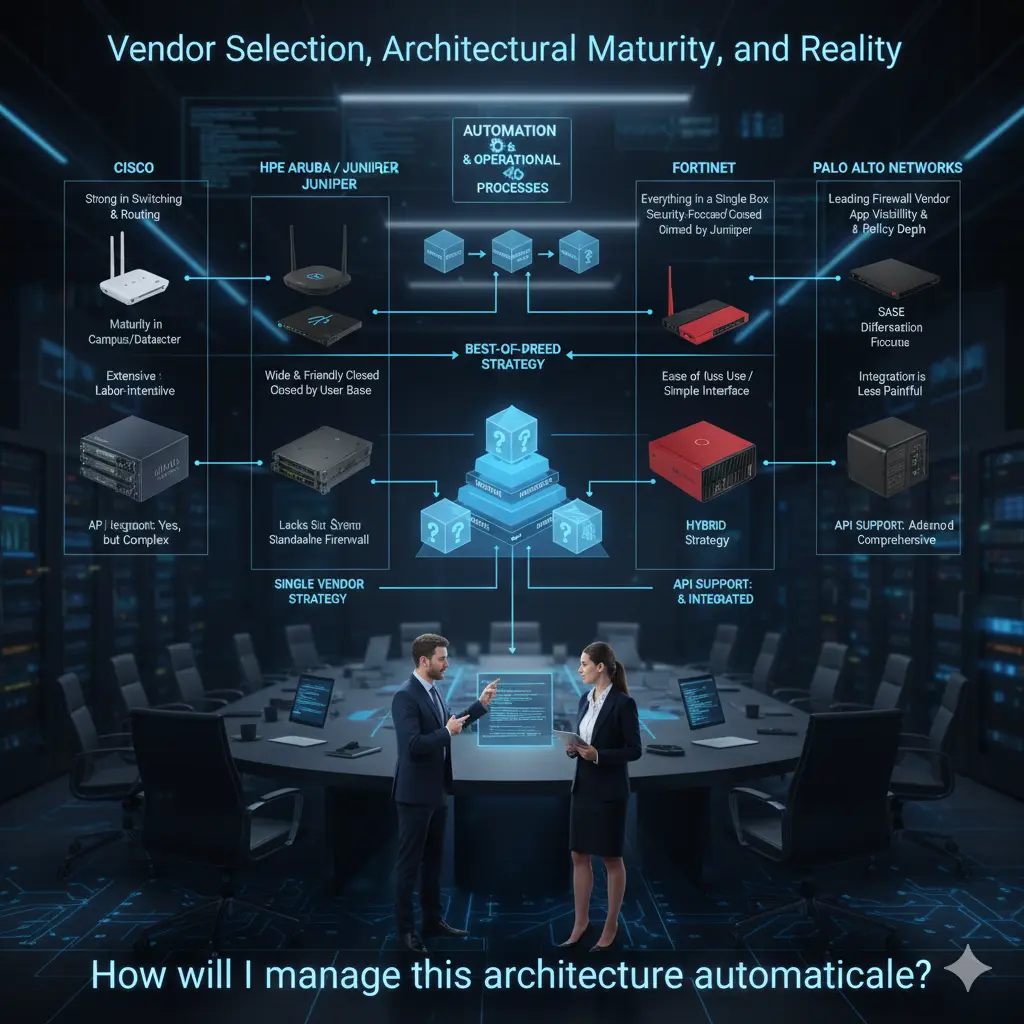

Closing: Vendor Selection, Architectural Maturity, and Reality

At this point, I want to clearly state that what I describe below is entirely based on my personal field experience and observations. My intention is not to praise or criticize any vendor, but to openly state where they are strong and where they struggle. Because core network design is not done with brand fanaticism, but with real needs and operational realities.

Starting with Cisco is natural. They are still one of the strongest players in switching and routing. Especially in large and complex environments, they have serious maturity in campus and datacenter switching. They have also been strong in wireless for many years, with a significant ecosystem and accumulated experience. On the firewall side, especially after expansions in Asian markets and acquisitions such as Power, they have shown serious development and are now in a more competitive position in the NGFW space.

However, it must be clearly stated: when you choose Cisco for everything, integrating these products with each other often becomes exhausting and labor-intensive for an administrator. Everything is possible, but it is rarely “easy”; integration requires significant effort and experience.

The HPE Aruba side, which I have followed closely for nearly a decade, tells a different story. When I first entered this ecosystem, the product portfolio was quite limited. Over time, with HP’s European acquisitions, the portfolio expanded; today, with the addition of the Juniper product family, it is growing significantly. On the switching side, the Aruba family has a wide and friendly user base. On the wireless side, influenced by its European-origin infrastructure, my personal view is that they offer one of the strongest Wi-Fi solutions in the industry.

In the past, there were gaps on the routing side; however, I believe these gaps will largely be closed with the Juniper product family. On the other hand, the lack of a strong standalone firewall product family causes them to fall somewhat short in this area.

Fortinet offers a very broad product portfolio. Their ability to provide a complete solution under a “single roof” across firewall, switching, and wireless is a significant advantage for many organizations. Due to Fortinet’s security-focused origins, they are known to be very strong on the firewall side. The switching product family matured later, which slowed its adoption, but in recent years it has appeared more frequently in the field.

In my view, one of the biggest advantages of the Fortinet ecosystem is ease of use and interface simplicity. Integration between products is relatively less painful, which can significantly reduce operational load. This difference is especially noticeable in organizations with limited IT teams.

When it comes to Palo Alto Networks, the picture is clearer: Palo Alto is very strong in firewalls and is unquestionably one of the leading vendors in this area. However, they deliberately do not enter areas such as switching or wireless; that is simply not their focus. Many organizations choose Palo Alto solely for firewall purposes, and there are very sound reasons for this.

I believe Palo Alto creates a serious difference in application visibility, policy depth, and especially in areas such as SASE. The fact that they are one of the world’s largest cybersecurity vendors today is no coincidence. It is entirely natural for many organizations seeking “the best” on the firewall side to gravitate toward Palo Alto.

In real life, companies make very different choices across these three main product groups. Some organizations prefer to move forward with a single vendor: switch, wireless, and firewall from the same brand; integration and support from a single point of contact; a clear counterpart when problems arise. Others choose one vendor for firewalls and another for switching and wireless. In more mature environments, selecting each layer from different vendors is also quite common.

These choices are often as organizational as they are technical. An organization’s view of IT, team structure, and the habits and past experiences of the network team significantly influence these decisions. There is no single right answer here.

My personal view is this: there are vendors who have proven themselves more strongly in specific areas, and if the IT team is mature enough to manage this distinction, selecting different vendors for different layers can produce much stronger technical results. On the other hand, some organizations prefer to move forward with a single vendor to avoid integration issues, installation complexity, and configuration errors, and to resolve all problems through a single support channel. This is also a completely valid approach.

Finally, there is one point I want to emphasize strongly: today, almost all major vendors are making serious investments in automation. At this point, API support is no longer an “extra,” but a direct selection criterion. What can be done via APIs, what can be automated, and how open the integration is must be on the table when selecting products.

As I mentioned in my first article, in my opinion, automation processes should not be considered as a layer added later during product selection. On the contrary, automation and operational processes should be placed at the top of the pyramid, and products should be selected according to this framework. The question of which switch, which firewall, and which AP should come after the question: “How will I manage this architecture automatically?” In my view, correct core network design starts exactly here.

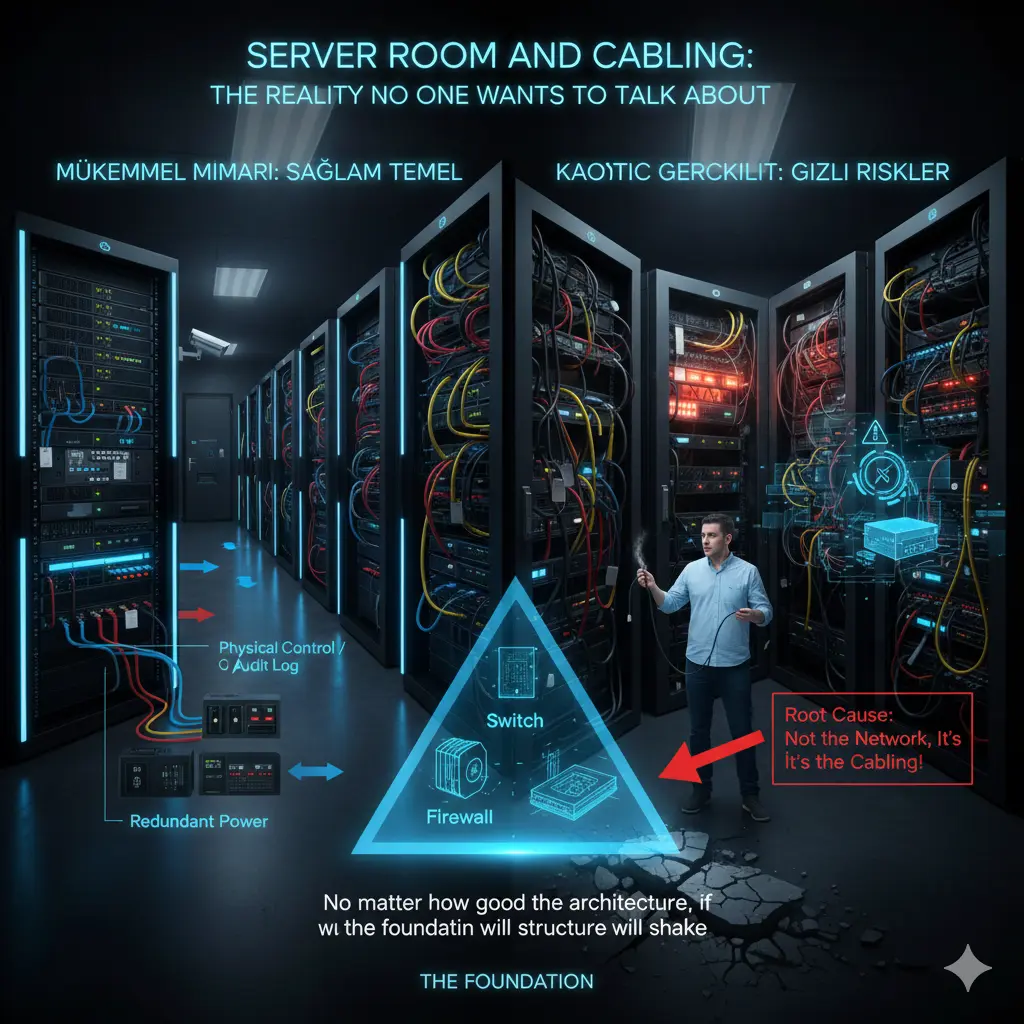

Server Room and Cabling: The Reality No One Wants to Talk About, but Everyone Pays For

In network projects, the most talked-about topics are usually the most “shiny” ones: which switch, which firewall, which wireless solution… But a significant portion of the problems experienced in the field start at a much more fundamental place than these products: server room design and cabling infrastructure.

There is one reality I have seen repeatedly over the years: no matter how good the products you choose, no matter how correctly you design the architecture; if the server room and cabling infrastructure are weak, that network will eventually produce problems. And these problems often appear as “network outages,” but the root cause is almost never the network itself.

In many organizations, the server room is still treated like a “storage room.” Initially, a few racks are placed in a small area; as operations grow, new devices are added to the same room, cables pile up, and temporary solutions become permanent. At some point, a space emerges that no one wants to touch, but everyone depends on. This is where the real risk begins.

A server room is not just a place where devices sit. It is the heart of the network. Heat, power, airflow, accessibility, and order must all be considered together. Cooling, for example, is often realized too late. Devices may seem to be working, but operating continuously at high temperatures significantly affects both performance and hardware lifespan. Sudden reboots, unexpected freezes, or “intermittent” issues are very often traced back to inadequate cooling.

The power side is similarly underestimated. Devices with redundant power supplies are purchased, but it is not verified whether these power supplies actually connect to different power lines. There is a UPS, but capacity calculations are not done. It is unclear how long systems will remain operational during a power outage. These may seem like small details on paper, but in a crisis, they render the entire architecture meaningless.

Cabling infrastructure is often thought of as something “done once and forgotten.” Yet cabling is the longest-lived component of the network. You change switches, firewalls, access points; but the cable remains. One of the biggest mistakes, therefore, is designing cabling based on today’s needs. An infrastructure planned for 1G today can hit a serious limit tomorrow with APs requiring 2.5G/5G uplinks or edge devices demanding higher speeds.

Deciding where to use fiber and where to use copper is also an architectural decision. Pulling fiber everywhere just because “fiber is faster” is not correct; there are still many cases where copper is advantageous, especially where PoE is required or distances are short. The real issue is designing cabling to allow for future expansion. Patch panel organization, cable labeling, rack-to-rack and in-rack cable management… These are not aesthetic concerns; they are operational ones.

Every change in a poorly labeled cabling infrastructure is a risk. You affect the wrong device when shutting down a port, you take down another service when unplugging a cable. Then people say, “the network went down again.” But the problem is not the network; it is the careless cabling done years ago.

Physical access security to the server room is also often overlooked. If it is not clear who can enter this room, at what times, and how changes are logged, even the best security policies lose their meaning at some point. In an environment where you cannot control physical access, discussing logical security often remains theoretical.

From my perspective, the server room and cabling are not the “lower layer” of core network design; they are the foundation. No matter how sophisticated the solutions you place on top, if the foundation is weak, the structure will shake. That is why when designing a network, it is necessary to look not only at diagrams, but also at the physical environment where those diagrams will be realized. Rack layout, cable paths, power, and cooling plans are all part of the architecture.

These topics are generally not exciting, they do not take up much space in presentations, and they are hard to put on a CV. But the truth is this: behind a well-functioning network, there is often a well-designed server room and a clean cabling infrastructure. No one notices this; because nothing goes wrong. And in my view, that is the greatest praise an infrastructure design can receive.

Not

This article was originally introduced on Substack in a shorter, narrative form. This version expands the architectural foundation for the series.

👉 Read the article on Substack: Click Here