The Monitoring Mindset: Not Just Seeing, But Understanding and Acting Proactively

Monitoring is a topic most IT teams talk about, but often implement incorrectly. When people hear “monitoring,” they usually think of a software tool, a dashboard, or red–green alert screens. However, monitoring is not just a set of tools or charts.

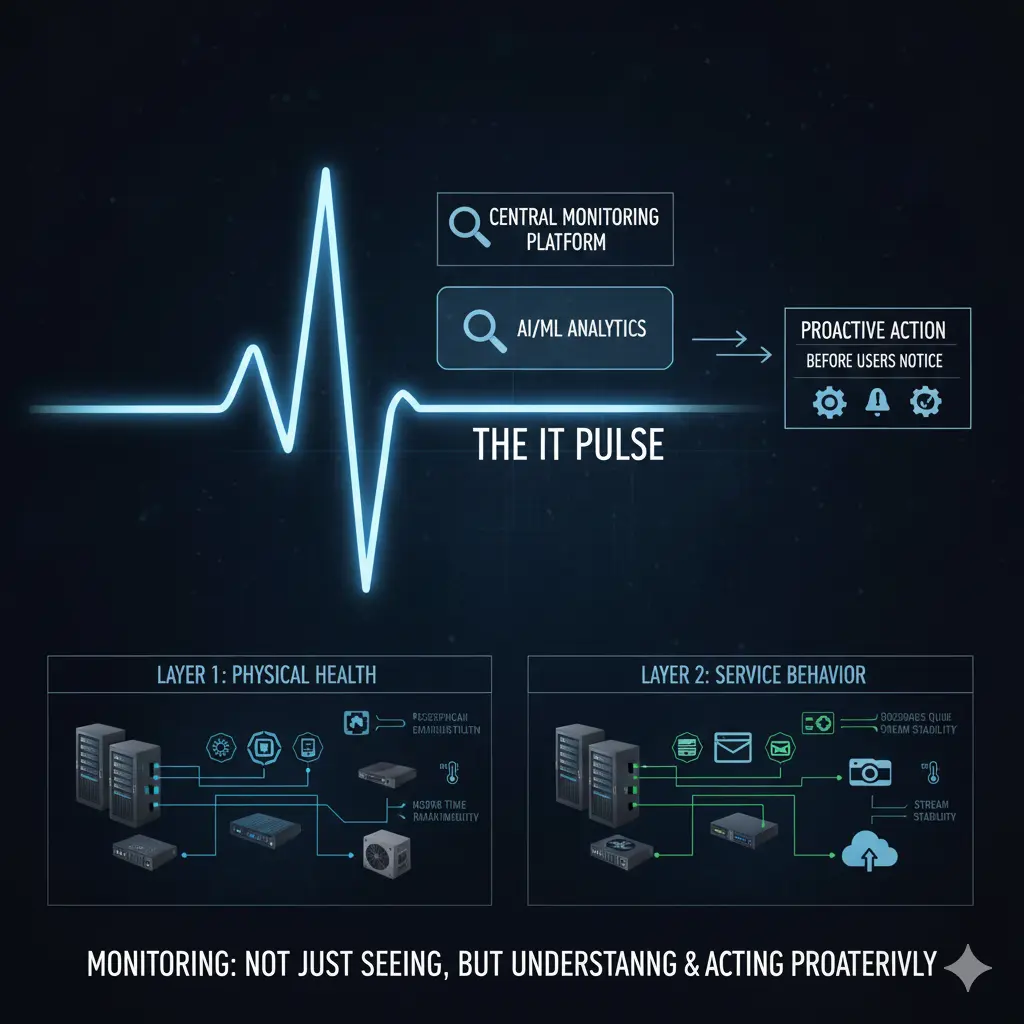

The real value of monitoring lies in detecting issues before users notice them and taking action proactively.

As IT infrastructures grow and diversify, asking “is everything working?” becomes meaningless. Modern infrastructures simultaneously include physical servers, virtualization platforms, network devices, firewalls, access points, and dozens of software systems running on top of them. Mail servers, file servers, camera systems, web applications, industry-specific business software… all must stay operational at the same time. This is where monitoring comes in: identifying issues before they fail.

To handle monitoring effectively, it is crucial to separate it into two layers: the physical infrastructure layer and the software/service layer. Without a clear distinction, monitoring can be incomplete or generate noise.

Physical infrastructure includes servers, network devices, firewalls, storage systems, access points, and the power and cooling components that keep them running. Problems in this layer usually start silently. A fan slows down, a power supply fluctuates, or a CPU stays at high usage for a long time. The system may be running, but it is not healthy. Monitoring here is about tracking health, not just “up/down” status. For example, a CPU running high or a slowly spinning fan means the system is technically active but at risk.

Key takeaways for this layer:

- Physical infrastructure problems often start silently

- Monitoring should focus on health indicators

Monitoring the physical infrastructure often starts with hardware-level metrics: CPU and memory usage, disk utilization, power supply status, fan speeds, temperature readings, and similar parameters. However, these metrics only make sense if the device operating systems are stable and properly configured.

For example, SNMP-based monitoring requires correctly defined SNMP configurations, proper access rights, and the necessary network permissions. Otherwise, a monitoring system exists, but the data is unreliable. Free solutions (like Zabbix) are very strong here; commercial solutions (SolarWinds, PRTG, etc.) typically offer easier setup and usability. Regardless of the tool, the tool itself does not solve the problem; correct metrics monitored with proper thresholds do.

Software and service layer monitoring is much more complex because every application has different behavior, load profiles, and critical thresholds. Response time is crucial for a web service, while queues and service status are more critical for a mail server. Disk I/O matters for a file server, while stream continuity and connection stability are key for a camera system.

Additionally, industry-specific software comes into play: reservation systems in hospitality, patient management systems in healthcare, production or automation software in manufacturing… Each is critical for business continuity and requires different monitoring approaches. Therefore, “one-size-fits-all” monitoring is impossible in the software layer. Monitoring must be tailored to the software’s function.

Key takeaways for this layer:

- Software monitoring cannot be generalized

- Must be designed according to business criticality

One main reason monitoring fails in many organizations is that it is not part of the operational routine. Systems are set up, monitoring tools are deployed, a few alerts are configured, and then, amidst daily operations, the structure fades into the background. Alerts are either ignored due to volume or never triggered, and problems are noticed only through user complaints.

Monitoring should be a process checked regularly. Daily checks can be done via a simple checklist or automated through tasks in an ITSM system. IT teams have daily or weekly routines, and monitoring checks should be deliberately included. If the company uses an ITSM or task management system, monitoring checks can be scheduled as recurring tasks and assigned to relevant personnel. This transforms monitoring from a “look if we can” approach into a measurable operational task.

Key points:

- Monitoring loses meaning if unchecked

- Monitoring must be part of the operational routine

Another significant effect: the time spent becomes visible. Spending an hour daily or a few hours weekly on monitoring is not wasted; it creates tangible evidence that IT operations are proactive. Problems are detected before they impact users, and IT teams are proven to work preventively, not reactively.

Centralized monitoring allows issues to be analyzed from a single point, reducing resolution time and enabling root cause analysis. When similar problems recur, discussions shift from “what happened” to “why it happened.” This is where true monitoring maturity begins.

Key points:

- Monitoring enables proactive, not reactive, work

- Time and effort become visible

Ultimately, monitoring requires the network, server, firewall, wireless, and software layers to be observed together, not in isolation. It’s not enough to monitor devices; the impact of these devices’ services on business processes must also be visible. A firewall may be running, but if users can’t send emails, monitoring fails. A switch may be up, but if access points keep losing connectivity, monitoring fails.

The real value of monitoring is making IT infrastructure behavior visible. This visibility enables better capacity planning, reduces change risks, and makes operations more predictable.

Key takeaways:

- Monitoring must be holistic

- Service behavior matters more than device status

Conclusion

Monitoring is not dashboards, alerts, or charts. Monitoring is taking the pulse of your infrastructure.

With a properly designed monitoring system, IT teams detect issues before users do, plan interventions, and manage infrastructure proactively. Monitoring becomes an operational and strategic competency, not just a technical detail.

It should not be a “set it and forget it” system; monitoring must be designed, operated, and continuously improved.