802.1X Projects: Deploying the Identity-Based Architecture in the Field

802.1X projects look like a network job from the outside; because the points of contact are switch ports, SSIDs, and RADIUS. But in real life, the success of 802.1X is often determined not on the network devices, but in the Active Directory structure, the certificate infrastructure (PKI), and endpoint management. The reason is simple: 802.1X forces the organization to talk about its “identity model” rather than just the port’s VLAN. In other words, you transition from “which port belongs to which VLAN” to a system of “which identity enters the network with what authority.”

This transition changes an organization’s habits. Because when 802.1X is deployed, the network is no longer something that “just works when you plug in a cable”; it produces results like quarantine for devices that fail validation, a portal for guests, or the wrong VLAN for a computer sitting in the wrong OU. This is why I see 802.1X not as a feature, but as an organizational capability: a capability where identity, inventory, policy, and operations sit at the same table.

Summary (Key Points Only):

- 802.1X is an identity architecture, not just port security.

- Success depends more on AD/PKI/endpoint discipline than on the network itself.

1) Planning: Without a VLAN plan, 802.1X becomes a “chaos engine” instead of a “policy engine”

When starting 802.1X, everyone’s first reflex is: “We’ll set up RADIUS, write it to the switch, and it’s done.” In the field, this usually ends with the very first pilot user. Because the pilot user connects, and suddenly this question arises: “Which VLAN will this user go to?” This is where 802.1X forces your hand.

If there is no meaningful VLAN/segmentation plan in the organization, all deficiencies become visible when 802.1X is deployed. If accounting and production are in the same segment, if cameras and user laptops are on the same network, or if the concept of a printer VLAN doesn’t exist at all; 802.1X cannot “automate” this structure, it will only make it “automatically wrong.”

Therefore, before the project starts, users and devices must be divided into “classes”: departments (accounting, finance, HR…), device types (printer, IP phone, camera, badge reader…), server segments (AD/DC, file, mail, web/DMZ), guest segment, quarantine segment. These segments are not just IP plans; they are the foundation of the access policy. For example, a user in the accounting VLAN should only access accounting applications and relevant file areas; even internet access should be differentiated according to company policy. While HR can access social media, finance might not. If these are “thought of later” after 802.1X, the project will never finish.

Summary:

- VLAN plan = policy plan.

- 802.1X makes the segmentation decision “un-postponable.”

2) Network readiness: Every VLAN must work manually before 802.1X is deployed

Before moving to 802.1X, it is not enough for VLANs to be defined on the switch and firewall; they must be manually tested. Because when a problem arises once 802.1X is active, it becomes difficult to isolate the root cause: Is the VLAN wrong, is a firewall rule missing, is RADIUS wrong, or is the certificate broken?

The workflow I recommend most in the field is this: Create the VLANs, set up the routing and firewall rules, then move a test port to a static VLAN and perform “expected access” tests with a user. If you created an accounting VLAN, is there access to the accounting application? Are file share permissions correct? Is the internet rule correct? Moving to 802.1X without passing this manual test is like driving a car blindfolded.

At this stage, the management network issue is also critical. Management IPs of switches, WLCs, and APs should be in a separate management VLAN. Even if 802.1X assigns the wrong VLAN, you shouldn’t lose access to your devices. If there is no “Management VLAN,” even during the 802.1X pilot, device management access is lost, causing very unnecessary crises.

Summary:

- You cannot proceed without manually testing VLAN + FW rules before 802.1X.

- If the management network is not separate, the project carries unnecessary risk.

3) AD side: Where there is no OU structure, 802.1X always turns into “exception management”

Now let’s come to the point you specifically pointed out: Active Directory OU structure. In 802.1X projects, one of the most critical points is “where” the classification of users and computers is done. In most organizations, users stay under Users and computers stay under Computers; departmental separation either doesn’t exist or is at the level of “visual arrangement.” When 802.1X is deployed, this structure is not enough. Because if you want to make VLAN assignment based on department, the department information must have a single source of truth.

The structure I see as “best practice” in the field is this: creating an OU structure for each department and keeping both the user and the computer under that OU. Because your goal is not just “user identity”; often, “corporate device” trust and departmental segmentation come together. If the user is under OU=Finance but the computer is scattered, GPO distribution breaks, certificate auto-enrollment breaks, and 802.1X policy matching breaks.

But there is a critical risk here: moving an OU is “not just drag and drop.” Moving a user elsewhere in the OU tree can change the GPOs applied to that user; login scripts, drive mapping, application distribution, and even the access model of some applications can be affected. Therefore, OU structure changes should be made in a controlled manner.

My recommended method: first select a single pilot user and pilot device from a single department. Do the OU move. Observe for 1 week–10 days. Because some accesses are not triggered every day in daily work; they are seen in the weekly process. For example, month-end finance reports, periodic accounting transactions, a special file share… These emerge during the pilot period. If problems arise, you make the OU/GPO corrections and then expand.

Summary:

- The OU structure is the invisible backbone of 802.1X.

- If OU movement is not done in a controlled manner, GPO/access side effects will occur.

4) Group Policy: “One-by-one manual setting” does not scale in 802.1X projects

You can set up 802.1X manually in the pilot; you cannot survive in production without GPO. Because the endpoints can be thousands of devices. Wired AutoConfig, WLAN AutoConfig, EAP settings, certificate selection, authentication priorities, user/device behavior… Managing these one by one manually is both error-prone and unsustainable.

Therefore, three things are usually done on the GPO side: First is the distribution of wired 802.1X profiles. On the Windows side, EAP type, auth mode, certificate selection, and validation behavior are centrally distributed with “Wired Network (IEEE 802.3) Policies.” Second is the wireless 802.1X profiles. SSID, security mode, EAP type, certificate requirements, and roaming behavior are distributed with “Wireless Network (IEEE 802.11) Policies.” Third is certificate auto-enrollment (I will explain this more deeply in the PKI section below). It is not realistic to scale certificate distribution without GPO. User certificate, computer certificate, and if necessary, the RADIUS server certificate chain… all must be managed automatically.

There is a small but very critical detail here: when “user-based 802.1X” and “computer-based 802.1X” are active at the same time, the order in which Windows will try them is important. In most designs, a model like “computer auth first, then user auth” is desired. Because if the device is a domain member, let the device be validated first, let the login screen come up, then let the permissions expand when the user logs in. This model works well for both security and operations—but if incorrectly set in GPO, it does the exact opposite and produces very strange problems.

Summary:

- 802.1X cannot be moved to production without GPO.

- Auth order (machine vs user) makes a difference in the field.

5) RADIUS / NPS / NAC: “Talking” is not enough; what answer it gives is important

The RADIUS side is seen by most teams as “We introduced the switch, gave the secret, it’s done.” This is only where the communication begins. The real issue is: what VLAN / what ACL / what policy response is RADIUS returning to the switch?

There are two worlds here:

- In the simple world, RADIUS only returns “accept/reject”, the VLAN remains static.

- In the mature world, RADIUS returns “accept” along with dynamic VLAN assignment, pushes dACL/ACL, and even changes port behavior with some vendor features.

Dynamic VLAN can also be done with NPS; in systems like Cisco ISE/ClearPass, you build a much more flexible policy engine. But the principle is the same: Identity and device information → policy → enforcement returning to the switch.

At this stage, a common mistake made in the field: using different IPs instead of the management IP when defining network devices as RADIUS clients, not being able to reach RADIUS due to the wrong VRF/route, source-interface errors… Then it’s said “802.1X is not working”; whereas the packet isn’t reaching RADIUS. This is why I start with the simplest test in every project: reachability from the switch to RADIUS, logs in RADIUS, then a test port.

There is also this critical distinction (you also mentioned): RADIUS is not only used for validating end users; it can also be used for admin login to network devices (TACACS+ is more suitable, but RADIUS is also seen in some structures). If these two use-cases get mixed up, wrong policies are applied to the wrong places. Since the focus of this article is endpoint access, the “device admin AAA” issue should be kept separate.

Summary:

- The project doesn’t end just because RADIUS “communicated”; “which policy response is returned” is important.

- Reachability/source-interface/VRF errors are the most classic root causes.

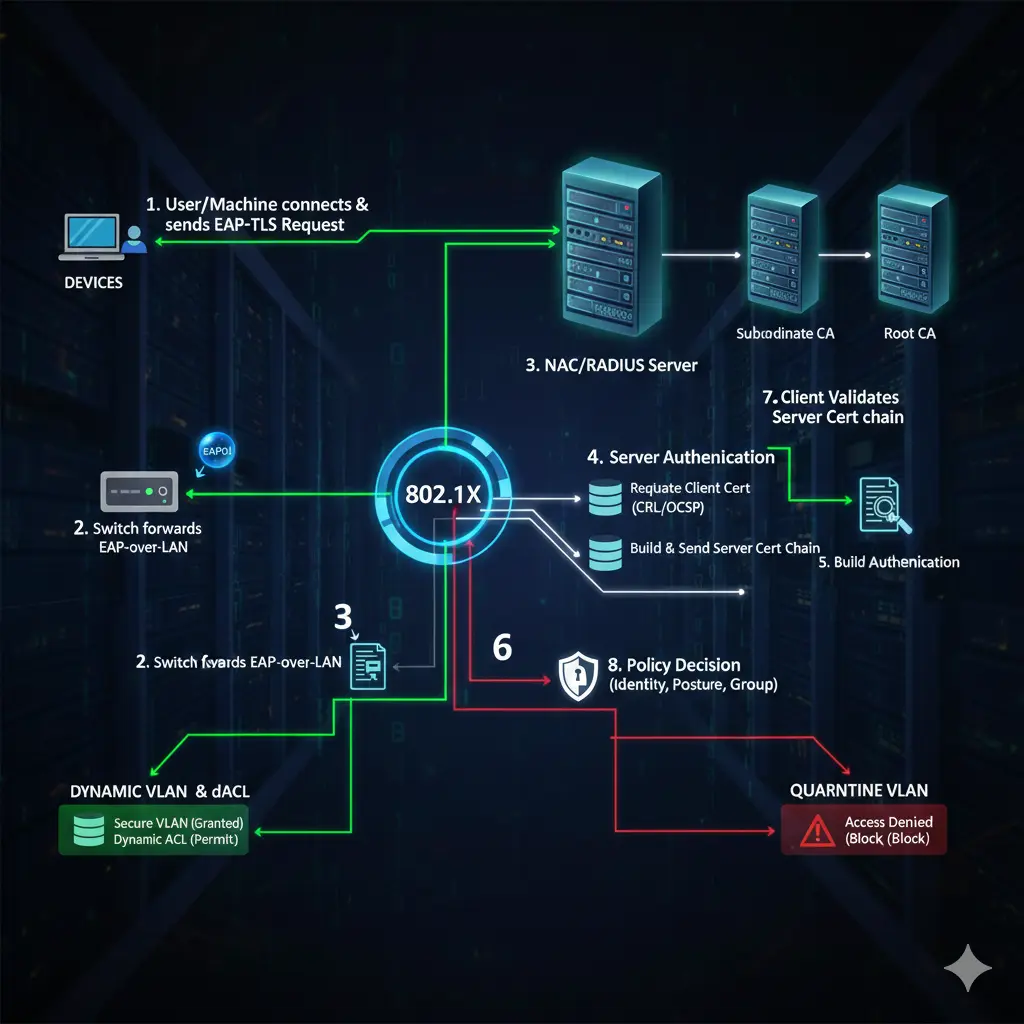

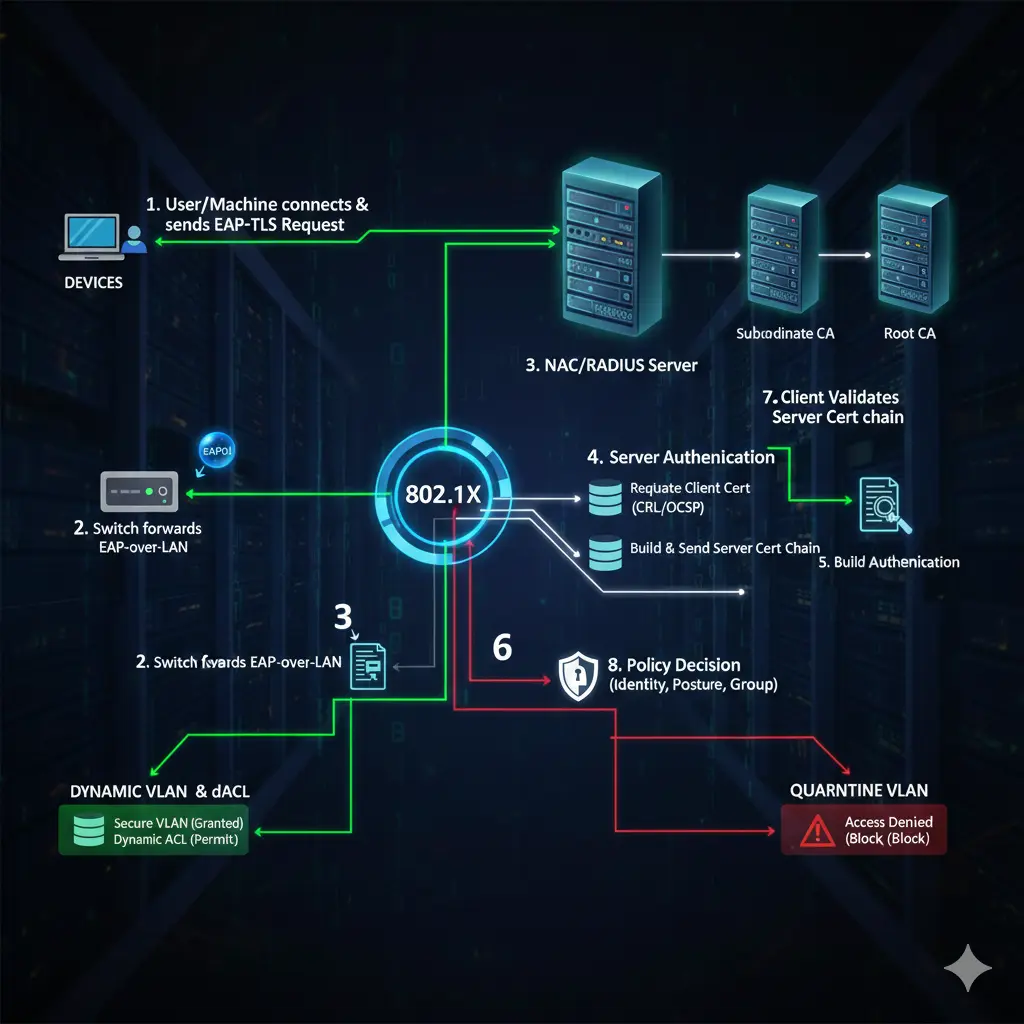

6) EAP methods: PEAP or EAP-TLS, Computer or User?

Now I come to the most critical technical part in your draft: “Which authentication model?”

Why PEAP (username/password) is practical but risky PEAP is easy: the user connects with their domain account. However, it creates a serious vulnerability in the field: a user can also enter the network from their personal laptop or phone with the same username/password. The “I already know the user” thought becomes insufficient at this point; because in the Zero Trust logic, the goal is to validate not just the user but also the device. This is why projects starting with PEAP usually evolve into TLS after a while “if the security goal is high.”

Why computer authentication is good but hurts in some organizations Computer validation requires joining the device to the domain. This naturally blocks personal devices. However, in places where shared computers are used (security unit, shipping, kiosk devices, etc.), it is not sufficient on its own if you want user-based segmentation. Because the same device remains in the same segment with different users.

Why EAP-TLS (certificate) is the “most correct” but why it requires discipline In EAP-TLS, identity comes with a certificate. This can be done both user-based and computer-based. Its strong side is: even if the password leaks, there is no access without the certificate. The weak side is that it requires discipline: the PKI being up, templates being correct, auto-enrollment working correctly, and CRL/OCSP access being healthy are factors.

There was a very correct piece of advice in your draft: let there be meaningful information like department/OU inside the certificate. This really makes a difference in the field. Because when you want to make mappings like “Finance OU → Finance VLAN” in the policy engine, the certificate content makes your job easier. Incorrect content pushes you back into the world of “manual mapping.”

Summary:

- PEAP is practical, but “corporate device” trust remains weak.

- Computer auth is strong but limited in shared PC scenarios.

- EAP-TLS is the most secure; PKI discipline is mandatory.

7) PKI and Certificate Templates: The silent breaking point of 802.1X

Now I’m going into the part you specifically called “quite missing”: Certificate Template, the distribution of the certificate, and RADIUS certificate validation.

If you are designing EAP-TLS, you have to think about at least two things on Windows Certificate Services (AD CS):

- Client certificates: (User certificate, Computer certificate)

- The server certificate that the RADIUS server (NPS/ISE/ClearPass) will present.

Distribution of client certificates is done with auto-enrollment in most structures. For this, a suitable template is prepared in AD CS, relevant “Enroll/Autoenroll” permissions are given to the correct groups, then auto-enrollment is activated with GPO. A very common error seen here in the field: the template is prepared, but because security permissions are wrong, the user/device cannot get the certificate; or it gets it but cannot be used in EAP-TLS due to the wrong EKU/KeyUsage.

Some of the things to be careful about on the template side are:

- Ability to use the certificate for “Client Authentication” purposes

- Whether the key is exportable (usually not desired)

- How the Subject/SAN field will be generated

- Whether it is produced for the user or the device

- Validity period and renewal behavior

- CRL access (validation crashes if it stays offline)

There was a very correct part in your draft: putting department/organization information into the certificate. This doesn’t mean embedding the OU directly into the certificate; but carrying a meaningful naming standard within the subject/SAN strengthens mapping on the NAC side. Because many institutions don’t do this, they later search logs for the answer to the question “who did this certificate belong to?”

Coming to the RADIUS side: NPS (or NAC) presents a server certificate to the client. If the client does not trust this certificate, it perceives it as a “man-in-the-middle” and does not connect. Therefore, the RADIUS server certificate chain (CA) should be distributed as trusted to the client. The practical way for this is again AD/GPO: you push the Root CA and intermediate CAs to the “Trusted Root Certification Authorities” area with GPO.

There is also the reverse direction: NPS may want to perform a CRL check while validating the certificate presented by the client. If CRL access is broken, validation is delayed or fails even if the certificate is correct. This detail is the classic reason for annoying “not connecting occasionally” problems in the field.

Summary:

- If template permissions/purposes are wrong, TLS ends.

- Auto-enrollment + CA trust distribution should be standardized with GPO.

- When CRL access crashes one day, everyone thinks “802.1X is broken.”

8) Dot1X and MAB together on the switch port: Writing the order correctly saves real lives

Another critical detail in your draft: there are usually two basic methods on the switch: dot1x and MAB (MAC Authentication Bypass). The most common and most logical model in the field is: try dot1x first; if dot1x fails, fall back to MAB. Because smart endpoints like laptops can do 802.1X; non-smart ones like printers/cameras can run with MAB.

Even a small configuration choice here makes a big difference in the field: when you prioritize MAB incorrectly, even a domain-joined laptop can connect with MAB and fall into the wrong VLAN; or vice versa, the printer can wait for a long time because it tried dot1x, giving the user the feeling of “no network.” Therefore, authentication order and event behaviors (fail-open/fail-close) should be chosen consciously in the port configuration.

Also, I emphasize the “proceeding on a port-by-port basis” approach again: in a place with 20 switches and hundreds of ports, taking every port to 802.1X in one day sounds very attractive but can wreck the project. The best method I’ve seen in the field: advancing department by department; first 1–2 pilot users in each department, 1 week of observation, then expansion.

Summary:

- Dot1X → MAB if fail order is the healthiest for most environments.

- Port-based controlled rollout finishes faster than a “one-day transition.”

9) Profiling: The “MAC only” era is over

MAC authentication is no longer sufficient security on its own. Because modern devices can do MAC randomization; it is easy to copy a MAC address. This is why advanced NAC solutions do profiling. The examples in your draft are correct: OUI check, DHCP fingerprint, CDP/LLDP, device description, and even HTTP User-Agent clues in some environments are evaluated together.

For example, when validating an IP phone, instead of just looking at the first 6 digits of the MAC; is the phrase “Cisco Phone” present in CDP, does model information come in LLDP, does the DHCP fingerprint look like a phone… When you combine these signals, you give a more reliable answer to the question “is this really a phone?” The same logic applies to printers. Thus, it becomes difficult for a fake device to take a VLAN via MAB by saying “I am a printer.”

Summary:

- MAC alone is not an identity; profiling approaches identity.

- Using multiple signals reduces abuse in the field.

10) Quarantine VLAN and Guest VLAN: They are not the same thing

Very few teams in the field set up this distinction correctly.

Quarantine: the company has the device/account, but it cannot pass validation. The password might be expired, the certificate might have expired, or the device might be domain-joined but stayed out of policy. The purpose of the Quarantine VLAN is not to “completely cut off” the device; it is to give the minimum access it can resolve the problem with. For example, let it access AD/CA, change the password, maybe get an update.

Guest: not the company’s device. It has nothing to do with the domain. Here you usually only allow internet; internal resources like AD/kerberos/LDAP are completely unnecessary. Due to the nature of Guest, the policy should be more “restricted but user-friendly.”

The wired/wireless difference in your draft is also important: on the wired side, the quarantine VLAN logic is easily applied (the port changes VLAN). On the wireless side, “denying connection” is more common in some designs than a quarantine VLAN; because the WLAN policy model is different. But I still like designs that have a “remediation” approach in wireless if possible—taking the user to a controlled network where they can solve the problem instead of hitting them against a wall completely speeds up the operation.

Summary:

- Quarantine is “ours but problematic”; Guest is “not ours.”

- Putting both in the same VLAN breaks security and operations in practice.

11) Guest portal: Sponsor login, SMS, social login, and the MAC randomization reality

Guest portals serve three purposes in practice: identifying the guest, giving a duration, and keeping records. The Sponsor login approach works very well, especially in corporate structures: the guest says “who I am visiting”; the system finds that person from AD; an approval mail/push is sent; once approved, the guest goes out to the internet. This both leaves a trail and removes the feeling of “open Wi-Fi.”

But there is a very important field reality in your draft: guest portals often identify the device with its MAC address. When modern phones do MAC randomization in Wi-Fi, the device may appear as a “new device” when the user turns Wi-Fi off and on and asks for validation again. This spoils the user experience. Therefore, in guest design, durations, portal behavior, and user information should be well planned. Otherwise, “internet is gone” calls rain down on the helpdesk.

Summary:

- The portal model is as much UX design as it is security.

- MAC randomization can break the guest flow; it should be designed accordingly.

12) Posture: The “last fortress” of 802.1X, but it tires operations if set up wrong

Now I am explaining in depth that “separate paragraph for Posture” matter you specifically wanted.

Posture is simply this: even if the user/device identity is correct, limiting access if the security status of the device is not suitable. In other words, adding the question “are you healthy?” next to the question “who are you?” This approach is very valuable, especially in devices coming from remote locations, laptops that haven’t received updates for a long time, or devices with AV turned off.

In posture control, typically the following are queried: OS version, patch level, disk encryption status, whether AV is present and up to date, whether the EDR agent is running, whether certain services are open, whether certain values exist in the registry, whether a certain file/folder exists. The reason these controls are valuable in the field is because corporate devices “drift over time.” People turn off updates, stop the agent, the AV license breaks, the device doesn’t see VPN for weeks. If you don’t catch this drift, you take devices with correct identity but weak security inside.

But posture has a price: often an agent is required on the endpoint. A new agent means; performance load, compatibility risk, user complaints, and deployment operations. This is why I find the approach in your draft correct: if possible, reuse the agents that are already installed instead of adding a “new agent.”

Examples are very clear in the field: In a Cisco environment, if AnyConnect (Secure Client) is already installed for VPN, NAC integration can be done with the posture module. On the Fortinet side, FortiClient can be used similarly as both a VPN and posture component. In some structures, EDR/AV agents like Trellix are already on every device; the NAC solution can integrate with these and pull the posture signal from here. But the critical point here is: posture does not automatically become “correct” just because there is integration. Which signal is reliable, what will be considered “compliant,” and in which case it will fall into quarantine should be clearly defined. Otherwise, posture suffocates the operation instead of increasing security: false positives, unnecessary quarantines, constant tickets.

The practical approach I recommend most in posture design is this: start posture as an “observation and reporting” mechanism in the first stage, not as a “deny” mechanism. That is, first collect the posture data, see how many devices come out non-compliant, then tighten the rules gradually. If you say “deny if AV is not up to date” on the first day, you can stop everyone’s work in the morning, especially in large structures. Posture matures in a process, not in one day.

Summary:

- Posture is a “identity + health” check; it catches the drift.

- A new agent is costly; it is smart to reuse existing agents.

- Not deny on the first day; measure first, then tighten.

13) Basic 802.1X → Profiling/Portal → Posture: Maturity levels

You classified this in the draft; I maintain the same logic but in an explained way:

For some institutions, the goal is just “let 802.1X work.” They start with simple dot1x/MAB; Windows NPS is enough. This model is low cost but its capabilities are limited. In a higher level, needs like profiling and guest portal come. Here NPS is no longer enough on its own; solutions like Cisco ISE, Aruba ClearPass come into play. At this level, the job is not just auth, but turns into “recognizing the device and managing the guest.” In the highest level comes posture. This level is the one with the most security return but also the highest operational cost. Therefore, when choosing posture, the organization’s endpoint management capability, agent strategy, and helpdesk capacity should be realistically evaluated.

Summary:

- Level 1: Dot1X + MAB (achievable with NPS)

- Level 2: Profiling + Guest (NAC is a must)

- Level 3: Posture (agent/integration + mature operation is a must)

Closing: 802.1X is not a “setup,” it is an internal contract

802.1X projects may technically look like a few commands on a switch or a few policies in RADIUS. But in reality, 802.1X mandates this contract within the institution: “How is identity carried, how is the device recognized, how is the guest managed, where does the problematic device fall, at what point does security begin?” If this contract is not there, the project is punctured by exceptions at some point, and in the end, everyone blames 802.1X.

The good projects I’ve seen in the field are the projects that accept this from the very beginning: the success of 802.1X is the sum of AD order, GPO discipline, PKI management, and a gradual rollout culture rather than the power of the devices. When you handle 802.1X like this, you don’t just increase security; you also centralize operations. And the real gain starts here.